Athletic Incontinence

Athletic Incontinence relates to urinary Incontinence experienced when you engage in high-impact or strenuous activity. A study by Carls (2007)[1] indicated that female athletes who participate in high-impact sports are at risk for urinary Incontinence and lack knowledge in young female athletes of preventative incontinence care. Abrams (2202)[3] defines Urinary Incontinence as "the complaint of any involuntary leakage of urine".

How common is Athletic Incontinence?

Nygaard (1994)[4], studying a group of college athletes, concluded that incontinence during physical stress is common in young, highly fit college female athletes. The study found that 28% reported urine loss while participating in their sport, with the highest proportions coming in gymnastics 67%, basketball 66%, tennis 50%, field hockey 42%, and track & field 29%.

Eliason (2002)[5] studied 35 elite trampolinists (range 12-22 years) and found approximately 80% of the trampolinists reported involuntary urinary leakage, but only during trampoline training. The leakage started after 2.5 years of training. Age, duration of the training, and training frequency all increased the risk. All women above 15 years of age reported urinary leakage.

Borin(2013)[7] evaluated the pressure of the pelvic floor muscles in female athletes. The group comprised 40 women between 18 and 30 years of age divided into four groups: ten volleyball players, ten handball players, ten basketball players, and ten non-athletes. Analysis of the data suggests that perineal pressure is decreased in female athletes compared with non-athletes. A lower perineal pressure correlates with increased urinary incontinence symptoms and pelvic floor dysfunction.

Addressing Athletic Incontinence

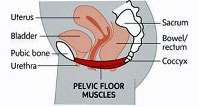

Athletic Incontinence is generally thought to result from the decreased structural support of the pelvic floor due to increased abdominal pressure during the activity.

The pelvic floor muscles lie transversely in the body between the pubic bone and the coccyx, acting as a "hammock" to support the abdominal contents and reproductive organs. |

|

In a study, BØ (1989)[8], showed that strengthening the pelvic floor muscles reduces urinary incontinence symptoms.

To address Athletic Incontinence BØ (2004)[2] recommends pelvic floor muscle training (Kegel exercises) as it has no serious adverse effects. In addition to strengthening the pelvic floor muscles, athletes should athletes should improve their Core Stability.

Kegel Exercises

The Mayo Clinic[6] explains how to perform Kegel exercises.

It takes diligence to identify your pelvic floor muscles and learn how to contract and relax them. Here are some pointers:

- Find the right muscles. To determine your pelvic floor muscles, stop urination midstream. If you succeed, you have got the right muscles.

- Perfect your technique. Once you have identified your pelvic floor muscles, empty your bladder and lie on your back. Tighten your pelvic floor muscles, hold the contraction for five seconds, and then relax for five seconds. Try it four or five times in a row. Work up to keeping the muscles contracted for 10 seconds at a time, resting for 10 seconds between contractions.

- Maintain your focus. For best results, focus on tightening only your pelvic floor muscles. Be careful not to flex the muscles in your abdomen, thighs or buttocks. Avoid holding your breath. Instead, breathe freely during the exercises.

-

Repeat 3 times a day. Aim for at least three sets of 10 repetitions a day.

Do not use Kegel exercises to start and stop your urine stream, as this can lead to incomplete emptying of the bladder, which increases the risk of a urinary tract infection.

Conclusion

BØ (2004)[2] indicates that there is no evidence to suggest that participation in regular, strenuous, high-impact exercise predisposes women to athletic Incontinence.

Perhaps modifying training programs to avoid fatiguing the pelvic floor muscles and introducing high-intensity jumping may help the pelvic floor muscles adapt and reduce athletic incontinence. Further research is required.

References

- CARLS, C. (2007) The Prevalence of Stress Urinary Incontinence in High School and College-Age Female Athletes in the Midwest: Implications for Education and Prevention, Urologic Nursing, 27 (1), p. 21-24, 39.

- BØ, K. (2004) Urinary incontinence, pelvic floor dysfunction, exercise and sport, Sports Medicine, 34 (7), p. 451-464

- ABRAMS, P. et al. (2002) The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: Report from the standardisation sub-committee of the international continence society, Am J Obstet Gynecol, 187, p. 116-126.

- NYGAARD, I.E. et al. (1994) Urinary incontinence in elite nulliparous athletes, Obstet Gynecol 84(2), p. 183-187

- ELIASSON, K. et al. (2002) Prevalence of stress incontinence in nulliparous elite trampolinists, Med Sci Sports, 12 (2), p. 106-110.

- Mayo Clinic (2014) Kegel exercises: A how-to guide for women. [WWW] Available from https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-living/womens-health/in-depth/kegel-exercises/art-20045283 [Accessed: 28th May 2014]

- BORIN, L. et al. (2013) Assessment of Pelvic Floor Muscle Pressure in Female Athletes, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 5 (3), p. 189–193

- BØ, K. et al. (1989) Female stress urinary incontinence and participation in different sport and social activities, Scand J Sports Sci, 11, p. 117-121

Page Reference

If you quote information from this page in your work, then the reference for this page is:

- MACKENZIE, B. (2013) Athletic Incontinence [WWW] Available from: https://www.brianmac.co.uk/athleticincon.htm [Accessed