Cyber Coaching

In 2011, a public row between British Athletics head coach Charles Van Commenee and former world triple jump champion Phillips Idowu hit the headlines. Van Commenee reportedly said that those who embraced 'Twitter' were "clowns and attention seekers", and Idowu took this criticism personally. The latter felt this was a direct criticism by the Dutchman of his decision to announce withdrawal from the European team championships in Sweden on that very same social networking site.

This incident raises the pertinent issue of modern technologies such as mobile phones, texts, emails, Facebook, and Skype in athlete-coach communication. In Athletics Weekly in August 2011, Dr Ross Lorimer articulated the importance of reliable communication between both parties as a precursor to success. The part that modern technologies play in facilitating or hindering this communication is paramount and worthy of consideration due to massive developments in the accessibility of mediated technologies over the last two decades.

Mediated communication

When we talk about mediated technologies, such as Facebook and texting, we refer to how the communication between the coach and their athletes is transmitted, the mediating factor between communicators. This mediator can change how communication is received and interpreted. Think about how you would feel about information whispered to you, and then think about it being shouted at you!

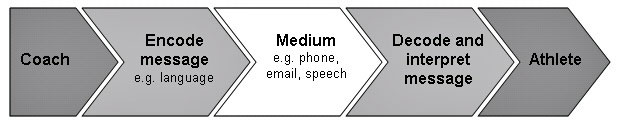

When coaches and athletes communicate, we encode our message in the language (e.g., our choice of words). It is then transmitted via a medium (e.g., speech, texting, or email). Finally, it is decoded from this medium and interpreted by the individual we communicate with (DeVito, 1994)[2]. Some people have difficulty deciphering the meaning behind a communication depending on the means or language used to transmit it. Individuals may use different words or terminology, or others may not understand the 'tone' of an email or text message. It can be because we are not familiar with the slang or are uncomfortable with the communication used.

Diagram 1. Mediated Communication (adapted from DeVito, 1994[2])

Lorimer and Jowett (2011)[6] stated that coaches and athletes must have 'shared meaning' to communicate and interact effectively. Hence, differences caused by age, the generation gap, and unfamiliarity with technology create the opportunity for miscommunication and conflict. Coaches and athletes must also remember that they provide more information than what they say or type when communicating.

How they speak is a form of communication in itself. So, texting someone could send the message that they do not have the time or desire to call and talk to them, or emailing athletes suggests that they are not as valued as athletes a coach sees at training.

DeVito (1994)[2] suggests that communication between individuals, such as coaches and athletes, has both a 'what' (the content) and a 'how' (the means of communicating). It has been argued that in sports, most coaches and athletes focus on the importance of the 'what', such as technical knowledge, tactics, interactions about goals, and developing skills.

However, the often-overlooked 'how' of communication is vital in achieving trust, respect, and understanding. The importance of how we communicate with each other cannot be overestimated and plays a crucial role in how healthy relationships form between coaches and their athletes. This relationship has been cited as a centre of athlete development and success.

Importance of communication in coach-athlete relationships

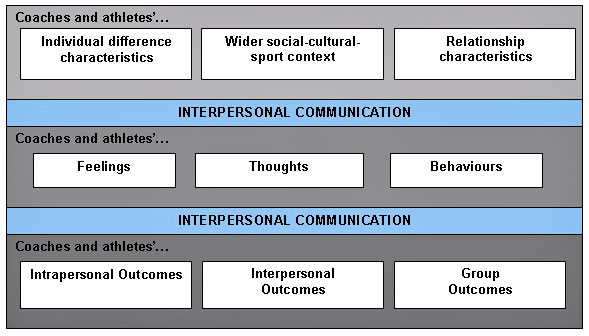

Jowett and Poczwardowski (2007)[5] have said that the relationship between the coach and an athlete is like the layers of a cake. The first layer includes the factors impacting the relationship, such as age, personality, roles, and expectations. The second layer is the quality of the relationship itself, as well as the nature and content of the partnership. The final layer gives the relationship outcomes, such as personal satisfaction and sports performance accomplishments.

Diagram 2. The coach-athlete relationship (Jowett & Poczwardowski, 2007)[5]

As can be seen from Diagram 2, the quality of the relationship is sandwiched between layers of communication. Jowett and Poczwardowski (2007)[5] suggest that this communication (the what and the how) is the glue that binds the coach and athlete's relationship. The quantity and type of communication used are central to either bringing them together or pushing them apart and bridging that relationship and their desired outcomes, such as personal performance.

Negatives of Electronic Media in the athlete-coach context

1. The synoptic effect

Mathieson (1997)[7] referred to the 'synoptic' society as one where the many can watch the few in a 'Big Brother' style voyeuristic context. Most of the coaches interviewed censured the specific medium of Facebook because it was 'too public'.

2. Over-responsibilisation of the athlete

The use of mediated technologies means that the athlete's communication skills have to be sound. According to Stanley, "There is a greater onus on the athlete to communicate instantly and succinctly. Initial thoughts can go off the boil in terms of communication after they have showered, eaten, and changed, and decided to contact you two hours later."

3. Demographics of utilisation

Mediated technologies have only become widely accessible in the last fifteen years, and their utilisation by both athlete and coach depends on the variables of social class, income, and age of both athlete and coach. They are increasingly popular but far from universal modes of communication.

Positives of electronic media in the athlete-coach context

1. Time-space distanciation

Giddens (1981)[4] coined this notion to explain how electronic media can instantaneously cut across time and space. Most of the coaches interviewed felt that text messaging was a great way of didactic or instructional communication regarding communicating updates and scheduling training sessions.

2. Data capture and retention

During the research, reference was made to the ability of athletes using Garmin technology to upload performance-related data and send it to their coaches and to the use of computers to avoid duplication in producing training schedules, which inevitably spawned a reliance on pen and paper.

3. Visual technologies

Morris pointed to the Internet-based video conferencing system 'Skype' as offering a medium whereby genuine two-way interaction between athlete and coach can be facilitated. He mentioned this about his athlete Emma Jackson, who represented Great Britain at the 2011 world championships in Korea.

Because of the visual and audio facility provided by Skype, Morris was able to conduct half-hour sessions with Jackson, who was in Daegu, where race tactics could be discussed. To endorse this point, Stanley mentioned his long-distance coaching of the Brazilian triple jump record holder, Jadel Gregorio, when the latter was in Brazil.

4. The panoptic effect

We mentioned earlier that the very public medium of Facebook exerts a 'synoptic' effect where the many can watch the few. Conversely, Foucault (1975)[3] wrote about the growth of the 'panoptic' society whereby the few can watch the many as with CCTV cameras. For all its dangers, Hadley mentioned that the utilisation of Facebook offered the coach an increasing opportunity to monitor the potentially inappropriate activities of athletes.

"Facebook reveals character and personality. If there are lifestyle concerns about the athlete, they reveal themselves to the coach. If young athletes use it too late at night, for instance, you can mention this to parents who can try to ensure that they are getting enough rest".

Differences between athletic disciplines

Although sprinting and field events place a high degree on biomechanics in their performance, Morris and Rush dismissed the assumption that face-to-face interaction was less critical for middle-distance and endurance coaches because they overlooked the myth that their events had less of a technical component. Significantly, Morris cited the example of needing to challenge an athlete about over-striding. The mythology can be expressed as follows:

| Event Typology | Technical Input Level | Remote Coaching Opportunity |

| Endurance | Low | High |

| Middle Distance | Moderate | Moderate |

| Sprinting | High | Low |

| Field Events | Very High | Very Low |

Diagram 3. The myth of remote coaching opportunity by event type (Long & Lorimer, 2012)[8]

Mind Games

Baudrillard (1983)[1] argued that we increasingly live in a postmodern world of 'hyper-reality' whereby illusion could easily be presented as reality. It was suggested that athletes using these social media sometimes did so to play 'mind games' to psyche out other athletes. Hadley passed the comment that "Facebook is part of the game. Athletes have to be savvy in terms of how they use it. It is foolish to tell others you have had a poor session at the track. On the other hand, 'beefing up' yourself is not always smart because ultimately you will get found out on race day".

Conclusion

While acknowledging the obvious benefits of mediated technologies, the coaches interviewed concluded that face-to-face interaction is the best regardless of the event type. They preferred to be both geographically proximate and time-bound, stressing that reading the athlete's body language during the session is vital to perceiving the intensity of effort.

"Whilst modern technology has uses, there is no substitute for visual and oral feedback". Martin Rush

"There is no substitute for the coach being there in real-time because there are times when you need to intervene". Peter Stanley.

In this postmodern world, mediated technologies are here to stay, and healthy coach-athlete relationships will employ a range of modes of communication. Mediated technologies can be used and not abused to facilitate interaction between the two.

Article background

The findings of this article were drawn from a series of semi-structured telephone interviews with the following athletics coaches and coach educators, all of whom have worked with Team GB athletes:

- Alan Morris. Coach to the world championship 800m semi-finalist Emma Jackson

- Martin Rush. National coach mentor -endurance and race walking

- Peter Stanley. National coach mentor- triple jump

- Tony Hadley. National coach mentor-sprints

References

- BAUDRILLARD, J. (1983) Simulations, New York. Semiotext(e)

- DEVITO, J. A. (1994) Human Communication: The Basic Course. New York. HarperCollins.

- FOUCAULT, M. (1975) Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison. New York. Random House.

- GIDDENS, A. (1981) Time-Space Distanciation and the Generation of Power. A Contemporary Critique of Historical Materialism: Power, Property and the State. London. Macmillan.

- JOWETT, S. and POCZWARDOWSKI, A. (2007) Understanding the coach-athlete relationship. In S. Jowett & D. Lavallee (Eds.), Social psychology in sport (p. 3-14). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics

- LORIMER, R. and JOWETT, S. (2011) Empathic accuracy, shared cognitive focus, and the assumptions of similarity made by coaches and athletes. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 42, p.40-54

- MATHIESEN, T. (1997) The Viewer Society: Michel Foucault's "Panopticon" Revisited. Theoretical Criminology, 1, p. 215-34

- LONG, M. and LORIMER, R. (2012) Cyber coaching, Athletics Weekly, 22nd March, p. 38-40

Article Reference

The information on this page is adapted from Long & Lorimer (2012)[8] with the kind permission of the authors and Athletics Weekly.

Page Reference

If you quote information from this page in your work, then the reference for this page is:

- LONG, M. and LORIMER, R. (2012) Cyber Coaching [WWW] Available from: https://www.brianmac.co.uk/articles/article079.htm [Accessed

About the Authors

Dr Matt Long works for British Athletics in coach education, having delivered work at the national high-performance centre at Loughborough University.

Dr Ross Lorimer is the Sports Science Programme Leader at the University of Abertay Dundee. He previously was a researcher at Loughborough University and has provided consultancy to Olympic-level coaches and athletes.