Food for thought

The fictitious legendary cartoon character Alf Tupper earned his reputation as the 'Tough of the Track' by winning races and smashing records on a diet of fish and chips. On the White City track, he could "run 'em all" after falling asleep on the train following the working of a late shift the night before. The days of this working-class hero are numbered, however, according to Senior Sports Scientist Eleanor Jones and English Institute of Sport nutritionist Mhairi Keil. They addressed a recent West Midlands regional workshop at Alexander Stadium.

Recovery

A gathering of some of the region's top endurance coaches and athletes heard Jones (High-Performance Centre, University of Birmingham) speak about training as the stimulus and recovery as the facilitator of adaptations, which would render the lifestyle of Tupper obsolete. Her message was that athletes must learn the basics before using more advanced recovery techniques.

| Basic recovery | Advanced recovery |

|---|---|

| Passive rest, sleeping, and school | Massage |

| Stretch | Relaxation techniques |

| Nutrition | Compression |

| Hydration | Hydrotherapy |

| Periodised & planned training | Ice Therapy |

"All athletes can get the basics right without a bank balance or specialist knowledge. For example, an ice bath can be detrimental to training adaptations, but in competition might be ideal," Eleanor Jones.

Nutrition

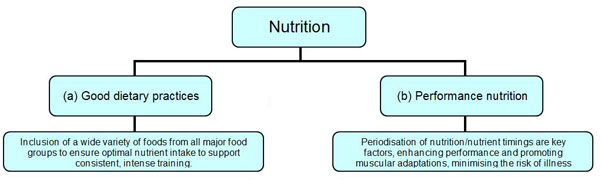

Nutrition is an inherent part of recovery, and Keil emphasised the need for coaches and athletes to understand the difference between good dietary practices and nutrition to enhance performance. See Figure 1.

Figure 1: Generic healthy diet versus performance diet

Having worked extensively with the British Gymnastics Association and supported 'On Camp With Kelly', Keil emphasised that the periodisation of nutrition is often overlooked (see Stellingwerff and Allanson, 2011)[3]. Keil maintained that daily fluctuations in macronutrient intake should vary according to duration and intensity to support training and recovery while maintaining a lean physique. In asserting that peak body composition and weight were not sustainable all year round, athletes were encouraged to note the difference between their 'training weight' and 'race weight'.

The concept was initially formulated in the early 1980s by Jenkins et al. (1981)[2]in medical research into diabetes. Foods with carbohydrates that break down quickly during digestion and quickly release glucose into the bloodstream have a high glycemic index.

Alternatively, foods with carbohydrates that break down more slowly with a more gradual release of glucose into the bloodstream tend to have a lower glycemic index. Keil stressed that the former should be used to boost blood sugar levels to gain energy quickly before training or competition, or promote fast recovery of muscle glycogen stores. Alternatively, the latter should be used outside of the immediate pre- and post-training period to help sustain energy and optimise nutrient intake (see Chiu et al. 2011)[4].

| High glycaemic index foods | Low glycaemic index foods |

| White bread | Sweet potato |

| Pasta | Milk |

| Cornflakes | Yoghurts |

| Chocolate bars | Fruits |

| Energy drinks/gels | Nuts |

Recovery should commence as soon as possible after training. The recommended period for nutrient intake is within 20-30 minutes, post-training, or as quickly as possible. Should this not occur, muscle recovery is impeded because it takes longer to appear.

Antioxidant requirements during heavy training loads were stressed, with berries, red peppers, beetroot, green tea, and olives cited as appropriate in this context. In confirming that iron is essential for haemoglobin formation and oxygen transformation, eating lean red meat two to three times per week was advocated.

Keil shared her observations from working with performance athletes across various sports. He noted that a common mistake was for athletes to inadvertently eat more on rest days than on active training days. Also, the mantra of 'More is not always better' was offered to take nutritional supplements because their inappropriate use and excessively high intake can be toxic and inhibit the absorption of other nutrients.

Conclusion

The workshop encouraged both athletes and coaches to reassess their practices on both recovery and nutrition in the following ways:

- Distinguishing between basic and advanced recovery techniques

- Understanding the necessity of moving from a generally healthy diet to a performance nutrition diet

- Evaluating when the intake of both high and low glycaemic index foods is appropriate

Article Reference

The information on this page is adapted from Long (2012)[1] with the kind permission of the author and Athletics Weekly.

References

- DR LONG, M. (2012) Food for thought, Athletics Weekly, 3rd May, p. 37

- JENKINS, D. et al. (1981) Glycemic index of foods: a physiological basis for carbohydrate exchange, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 34 (3): p. 362-366

- STELLINGWERFF, T. and ALLANSON, B. (2011) Nutrition for Middle-Distance and Speed-Endurance Training, in Sport and Exercise Nutrition (eds S. A. Lanham-New, S. J. Stear, S. M. Shirreffs and A. L. Collins), Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, UK.

- CHIU, C. et al. (2011), Informing food choices and health outcomes by use of the dietary glycemic index. Nutrition Reviews, 69 (4): p. 231–242

Page Reference

If you quote information from this page in your work, then the reference for this page is:

- LONG, M. (2013) Food for thought [WWW] Available from: https://www.brianmac.co.uk/articles/article126.htm [Accessed

About the Author

Dr Matt Long is a British Athletics Coach Education Tutor and volunteer endurance coach with Birmingham University Athletics Club.