Mastering the Boards

With the significant indoor championships during the winter almost upon us, the man who finished 4th in the world indoor championship 1,500m final in Budapest in 2004 gives an insight into the specific demands of mastering the boards in the context of a double peak periodisation of training.

Accessibility of indoor athletics

The 2006 AAA's indoor 3,000m champion starts by reminding readers that indoor running is far more common than it was twenty years ago. It is because of the development of tracks associated with high-performance centres across the country, such as the UWIC facility in Thie's home city of Cardiff. "I used the UWIC facility as a student because it was a mile from where I lived. It was one of the first facilities to be used in the UK. It is no coincidence that Wales has produced some excellent indoor athletes such as Joe Thomas and Jimmy Watkins, who have thrived indoors due to that same facility".

Stepping stone

The Melbourne and Delhi Commonwealth Games Welsh representative says, "It's a great stepping stone for athletes to get their foot on the international ladder. Remember that world indoor qualifying times are slower than for the outdoor championships. The tragedy is that some athletes deliberately opt out of the indoors to concentrate on the summer season and then end up not qualifying for the outdoor championships". He encourages up-and-coming athletes to reflect on the fact that indoor competition can be, "a great stepping stone in terms of bridging the gap and heading towards selection for outdoor championships".

Double peak periodisation

In tracing the roots of the periodisation theory, one has to acknowledge the contribution made by the endocrinologist Hans Selye. His research on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA axis) system in the 1950s informed the development of General Adaptation Syndrome in understanding how human beings respond to stress.

A decade later, Russian professor Leonid Matveyev is credited with applying this work to an athletic context in terms of developing the notions of distinctive blocks of training over time and laying the foundations for what is nowadays commonly referred to as 'macro' (months), 'meso' (weeks) and 'microcycles' (days) of training.

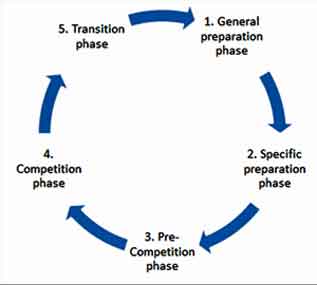

Matveyev was at the forefront of pioneering research into how the coach could manipulate training volume, intensity, and specificity at different points in time to enhance athletic performance within a single peak periodised macrocycle of training (See Figure 1). re 1).

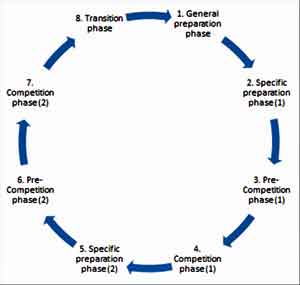

In concluding that for some athletics disciplines, two periods of competition in one year allowed for sustaining both higher and more specific training intensities, Medveyev advocated double peak periodisation of the kind needed for the athlete contemplating an indoor as well as an outdoor season (See Figure 2).

Debate still rages in the sports science community about whether double peak periodisation suits all contexts. It is deemed inappropriate for endurance events for some because of the time needed to build an aerobic base before a successful competition. For others, double peak periodisation should be used selectively throughout an athlete's career, with a recommendation not to be undertaken yearly without careful thought.

Figure 1 - Single Periodised Plan |

Figure 2 - Double Periodised Plan |

Before discussing the physical demands of indoor racing, the Director of Athletics at Cardiff Metropolitan University tells me, “Mentally, 12 months is a long time to train without competing. I can never understand athletes who seem to train to do more training. An indoor season gives you that mental stimulation.”

When challenged as to whether a successful indoor season can be compatible with success outdoors, he is adamant that “Andrew Osagie could not have made the Olympic final and run 1m 43.7 seconds without enjoying his success in taking world indoor bronze in Istanbul. You can bring your body to a peak twice in one year”. With a 1,500m indoor best of 3 minutes 38.69 seconds set in Birmingham in 2004, he tells me he remains an admirer of the 5-pace system developed by the late BMC founder Frank Horwill.

“I used the system in two basic stages”, he says. “I worked at the half-marathon, 10k, 5k, 3km, and 1,500m paces in training before Christmas. After Christmas, I still used a multi-paced system but worked at 5k, 3k, 1500m, 800m, and 400m paces in my training”.

In terms of peaking for indoor championships, he advises middle distance and endurance athletes precisely that, “You've got to come off the volume and taper. However, if the world indoors is in March, it still gives you three months to recover and build towards outdoor success from June onwards”.

While crediting the early guidance of Tom Watson and the later influence of Mark Rowlands, Thie remains self-coached as an active athlete with aspirations of reaching his 3rd Commonwealth Games in Glasgow in 2014.

He says, “Athletes should remember that the indoors are an intense 6-week season. It's a much shorter block of competition than the outdoor season”.

Technical

A well-respected coach, Thie's indoor prowess has rubbed off on his training group, as evidenced by his guiding under-23 athlete Charlotte Arter to BUCS indoor gold over the metric mile (4 minutes 22.5 seconds) in February 2012. "There's no sun and wind indoors, so you don't have to deal with unpredictable British weather", he laughs. "It is a far more controlled environment indoors than outdoors", he adds.

"There are certain kinds of athletes who will always struggle indoors, but that does not mean they should not still give it a go", he enthuses. "Taller athletes who need space to operate are at a disadvantage. The indoors suited my physiology. I have no long, rangy stride and like running the banks.

I tied to perfect slingshot off those bends," he adds passionately. "I loved the physicality of indoor racing and had no qualms about using my elbows when needed. It comes with the territory".

Thie maintains that with practice, athletes can adapt their cadence for the demands of indoor racing and uses the analogy of needing to "change down through the gears as you go around the bend". In terms of modelling best practice, Thie has no hesitation in pointing to the three-time world indoor 3,000m champion, Bernard Lagat, as the master.

"Lagat is the best I have ever seen. I remember running the mile against him at the Millrose Games in New York. It was this tiny 180-metre track, and I was stride for stride with Alan Webb (American record holder 1 mile - 3 minutes 46.91 seconds). We both looked across in sheer disbelief and could see Lagat half a lap ahead of us!" he adds ruefully.

Tactical

The man who is the competition manager for Welsh Athletics maintains that indoor racing requires a very different tactical approach from outdoors. "With the middle distance and endurance events, it is all about getting the first 3 or 4 laps out of the way and avoiding an incident," he stresses. "Competitions are overwhelmingly slower and more tactical, with the third quarter of the race becoming crucial in positioning to launch an attack. The outright race for home tends to begin in earnest only in that third quarter".

In reflecting on his utilisation of multi-pace training, he encourages athletes to consider that "Middle distance and endurance races are rarely run at even pace indoors. Multiple changes of pace are inherent. When I finished 5th in the world indoors in Budapest (3 minutes 53.36 seconds), we jogged through the first 800 metres in about 2 minutes 15 seconds.

The last 400 metres were ridiculous, like 52.9 seconds, a year later, in the European indoors in Madrid (where he placed 6th in 3 minutes 40.76 seconds). I had to go through 800 metres in 1 minute 56 seconds because the race was won in around 3 minutes 35 seconds. You have to respond to both of the above scenarios tactically.

The man, who hails originally from the North Somerset town of Clevedon, adds that the timing of the sprint finish is paramount in indoor middle-distance and endurance racing. "In domestic races, I preferred to strike about 170 metres from home on the penultimate bend. At this point, it was always difficult for my rivals to return and overtake me.

Again, the point I am making is that your preference for striking for home indoors may be markedly different from outdoors, where the straights are longer and the bends less severe. It needs both planning and practice to execute the art".

Conclusions

As he laces up his spikes and prepares to embark on a session of 15 x 200 metres with just 30 seconds recovery between repetitions, his parting shot is a word of encouragement to all those athletes considering dipping their proverbial toe into the water of indoor racing. "Remember, Bekele ran indoors, and so does Mo Farah, and if it is good enough for Mo, it is good enough for you!" he implores.

As I stand on the Alexander stadium track and time his 200-metre efforts, the 34-year-old hits everyone in a metronomic 30 seconds. If you see Thie pulling on the red vest of Wales for his 3rd Commonwealth Games in Glasgow in 2014, remember that much of his work will have been done on the boards of that UWIC facility, which he has called home for almost half of his life.

Article Reference

The information on this page is adapted from Long (2013)[1] with the author's kind permission and Athletics Weekly.

References

- LONG, M. (2013) The Board Game, Athletics Weekly, 10th January

Page Reference

If you quote information from this page in your work, then the reference for this page is:

- LONG, M. (2013) Mastering the Boards [WWW] Available from: https://www.brianmac.co.uk/articles/article155.htm [Accessed

About the Author

Dr Matt Long is a British Athletics Coach Education Tutor and volunteer coach with Birmingham University AC.